This is Part 6 in a series about the 50th anniversary of the War on Poverty. Click here for Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5.

—-

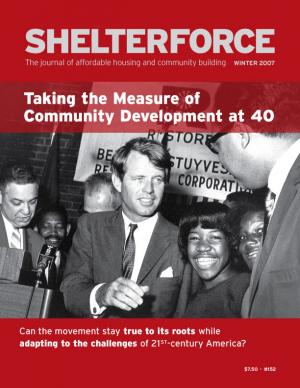

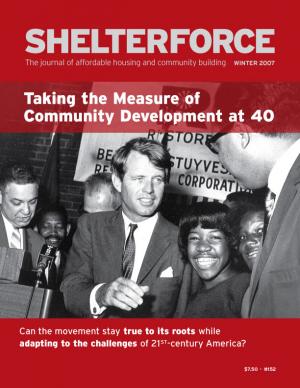

The first legislation enacting the War on Poverty was the 1964 Economic Opportunity Act. In 1966, New York Senators Robert Kennedy and Jacob Javits introduced an amendment to the Economic Opportunity Act that ended up creating the first official, federally recognized Community Development Corporations (CDCs). Community development actually has deeper, older roots than this 1966 legislation, but this was when CDCs went official and were taken to a bigger, broader stage.

But, despite this common origin in the Economic Opportunity Act, you can see tensions between community development and the War on Poverty—the tension between the president and his desire to own the poverty issue and Robert Kennedy, the Camelot heir who and presumed prime challenger for the presidential nomination.

On one side you had the Kennedys’ rhetoric around entrepreneurialism, about new ideas, about the mixing of private and public efforts to solve problems (The formulation of community development entities as “corporations,” for example, was said to be something important to RFK in that it was a rhetorical way to bridge community and business interests and to make community action palatable to a wider audience). On the other side, there was LBJ, a former New Deal congressman, who saw things in terms of big, top down entitlement programs (the Food Stamp Act of 1964, the Social Security Act of 1965, which created Medicare and Medicaid) and deals between political players.

Obviously, this is a gross over-simplification. Johnson’s War on Poverty contained many component parts that were directly related to community development (Model Cities, the Office of Economic Opportunity); community development had many roots and traditions long before RFK ever stepped foot in Bed-Stuy; and, RFK, of course, was a political player who did backroom deals. But the larger point stands. Community development and the War on Poverty are deeply linked though not in complete harmony.

The Once and Future Community Development

The first official CDCs of the late 1960s were a diverse set of organizations, with diverse and varied programming. CDCs were known for an approach that was both entrepreneurial and grassroots. A roll-up your sleeves, do whatever it takes approach to working and building community in low-income neighborhoods. But, over time, as the commitment to the War on Poverty waned, the set of programs and funding that supported CDCs shrank and narrowed. Likewise, the field of community development became more and more about affordable housing production, particularly starting in the 1980s, with the introduction of the Low Income Housing Tax Credit. A little bit for the better but mostly for the worse, the field became more professional, more technocratic, more buttoned down, more capital intensive.

In the pieces I’ve written about the history and current state of community development, I always talk about how community development needs to return to its grassroots and people-and-place-centered roots. This Back-to-the-Future of community development should happen while adding a more explicit and central commitment to economic justice and taking advantage of some of the latest in terms of technology (using social media as an organizing tool) and accountability (improved metrics across a broader array of programs).

Community Development and Economic Justice Metrics

Community development should be looking to affect results across statistics (big and small) that rest in individuals—statistics having to do with health, educational attainment, job safety, hours spent working, job benefits, physical mobility, time spent stuck in traffic, ability of low income people to have time spent with friends and family (family defined broadly), ability to respond to and weather the inevitable personal/family/financial/health crises, etc. Through the results we generate, we would show the dependence of these individual-level metrics upon community-level factors such as:

- Social and Cultural Infrastructure: Presence, accessibility and health of community-based, cultural, social and faith-based organizations/institutions that serve low-income people;

- Neighborhood Infrastructure: Sustainability, livability, walkability, health, economic vitality and safety of the places where low-income people live – including access to quality, healthy food, quality affordable housing, recreational opportunities, jobs, good schools, mass transit;

- Civic Engagement: Participation in civic society, power/ability to influence outcomes, activities and resource distribution in places where we live, work, worship (if choose to) and where our children play, grow, are educated;

- Community Empowerment: Ability to form community and common goals around interests and identity and for these communities of interest/identity to have impact and meaning in broader society; ability and opportunity to organize; opportunity and power to work towards a greater good.

Not every program/activity can or should be held to the aggregate of these outcomes. But the aggregate of community development can and should show results across all of these measures.

The Next 50 Years

As we celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the War on Poverty, at this troubled and troubling historic moment, we find ourselves in the unfortunate position of having to defend the entirety of programs that serve low-income people – of having to defend the very notion of serving low-income people. But we can’t just get stuck playing defense. We also have to articulate a prospective, positive vision of economic justice that can move us forward. And, for those of us who self-segregate into sub-fields, we need to show how our areas of work support the larger vision. But we shouldn’t do so in a way that denigrates or diminishes other fields, other allies’ modes of work.

To make progress, we’re going to need lots of different people working in lots of different ways and we’re going to have to communicate and coordinate better than ever before between fields of work. We’ve got a lot to do. But it’s worth doing. So let’s get to it…

I love your attitude, it reminds me that it is still about rolling up our sleeves and just getting to it! Though Community Development programs have become more complex and stratified, in the spirit of those early days of Community Development, we should prioritize innovation of new ideas and approaches.

As someone who works at a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI – a small business loan fund) housed at a Community Action Agency (Fresno EOC), I live the tension between the war on poverty and community development every day! The goal of poverty alleviation amid the pressure to preserve limited resources/capital can be tricky to say the least. Lending money to poor people carries inherent risk – but when fighting the war on poverty, it’s a risk that needs to be taken (wisely).

As someone who has been with a CDFI since its inception 6 years ago, I have experienced the transition from the ‘roll up your sleeves do whatever it takes’ modus operandi, towards a ‘more professional, more technocratic, more buttoned down, more capital intensive’ way of doing business. Believe me I’m nostalgic many a day – and its really a balance that needs to be struck between the two. However, it seems that development tends toward complexity and not stasis. As we expanded from $700,000 to $7 million in loan funds, and deals got more and more complex, we had to adapt or die.

Jeremy Hofer

Business Development Manager

http://www.fresnocdfi.com