Innocent.

The city exploded in flames. Lives were lost. Billions of dollars’ worth of property was destroyed. Businesses were shuttered, forever. The dreams of aspiring Asian merchants were also crushed in a community uprising against persistent poverty and injustice.

What we witnessed in Baltimore is, in many ways, the same as in 1992, sparked by the recent string of events in Florida, Los Angeles, Ferguson and New York. It was certainly a response to dreams deferred—for too long, and for too many. It was also a provocation, a frontal assault against injustice. And when the Humvees roll away and the volunteers have finished sweeping up the broken bottles—it will become a test of that city’s resilience.

Resilience is a word we hear a lot lately, most often applied to communities devastated by weather-related disasters like Hurricanes Sandy and Katrina, which have become increasingly common in the era of climate change. It also applies to cities, like Baltimore, that are reeling from civic unrest.

But what does resilience mean, exactly? How can our cities prevent—and recover from—disasters, whether natural or human-made? As we confront the existential threat of climate change in a world of widening inequality, it is a question with urgent relevance.

So, here are a few answers worth considering, gleaned from decades of work in community development and from the newer field of climate resilience. They relate to the three phases of resilience planning: mitigation, response and recovery.

- Lesson one: Mitigation matters. The best defense against any disaster is to anticipate and prevent it. For both climate disasters and civic unrest, we have the tools to do so—if we choose to use them.

Climate science enables us to isolate risk factors and predict the probability, frequency, location and degree of risks—such as melting ice caps, rising sea levels, hurricanes and tornadoes. This increasingly sophisticated science has driven many world leaders to work to mitigate climate change by advancing policies, technologies and investments that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The more prudent leaders among them also anticipate and prepare for the disasters that are now inevitable by rebuilding infrastructure—transportation, communication, food, and emergency response—to withstand extreme conditions.

The social sciences provide a similar set of tools. We may be able to predict the next Baltimore or Ferguson by examining incarceration rates, or the depth and persistence of income, health and educational disparities. And we can mitigate future crises by confronting underlying issues: the lack of human rights, social justice and economic opportunity that crush the dreams of low-income, predominantly people of color.

If we have the facts, why are we not unified around and proactively working to remove the stressors that inevitably lead to disasters? While the resilience of the African-American community is well proven, how can we not anticipate urban disturbances, given our long human history of exploitation and subjugation? The Baltimore disturbance was a predictable response to dreams deferred. The surprise, indignation, and victim blame for the eruption was as egregious as the failure to try to prevent the disaster in the first place.

- Lesson two: Community preparedness is essential. What do we do when our levees or emotions break? How do we bring order to inevitable chaos and confusion after a disaster?

The Baltimore story shows that ‘‘hardening” tactics—fortifying police with rifles and riot gear—are not as effective as community-driven management. While the arrival of the National Guard escalated an already tense situation, it was the people of Baltimore who stemmed the violence, sent home rioters, cleaned up the streets, managed vehicular traffic, negotiated peace, calmed hysteria, and provided factual commentary in the face of hyped media reporting.

This has proven true in climate-related disasters, as well. Efforts to harden cities against disaster with things such as levees and seawalls can be effective—but they eventually fail. At that point, community response can literally mean the difference between life and death.

The key lesson here is that fortification is no substitute for community engagement and preparedness. In fact, fortification can provide a false sense of security, leaving communities unprepared for disaster. And yet, to our peril, we underinvest in equipping our communities to effectively engage in disaster response.

- Lesson three: Build resilience with cooperative economics. In Baltimore and beyond, we see that communities come together in crisis, crossing natural and artificial boundaries, including gang territories, generations, religion, race, ethnicity, and geography. We can invest in this collective human capacity to not only rebuild what disaster destroyed, but to create a more generative and protected society.

“Cooperative economics” is one way to do so. Cooperative economic enterprises are organized to benefit workers, communities and consumers—not just to maximize profits for shareholders. As documented in Jessica Nembhard’s book, Collective Courage, the African-American community has a special history with cooperative economics, which protected threatened communities from economic and social disasters, and also helped them to thrive until they were destroyed by threatened competing economic interests.

Today, the cooperative movement is re-emerging as one important response to building climate and urban resilience. Worker, food, housing and energy co-ops can help restructure and rebuild the economic, physical and social resilience of our communities. For example, the Evergreen Cooperatives of Cleveland, Ohio create green jobs that pay a living wage. Evergreen’s employee-owned, for-profit companies—laundry services, urban agriculture, and renewable energy—are linked to the supply chains of the city’s anchor institutions, which helps keep financial resources in the community. Evergreen builds resilience by protecting workers from the vicissitudes of the global economy, and also by protecting the ecosystems on which the city depends.

The recent events in Baltimore offer important lessons in crisis mitigation, response and recovery. Those lessons are especially important in the era of climate change, as weather-related disasters are layered on top of long-standing crises of inequality and despair. And those lessons apply beyond the hardest-hit low-income neighborhoods. The fact is, climate change strikes at the core of our basic material and emotional needs. It affects our food and water supply, quality of life and health, livelihood and lifestyle and overall sense of safety and certainty. Climate change is manifesting as the American Dream deferred—for everyone.

And yet, Baltimore shows us that a dream deferred does not have to fester, dry up, sag or explode. It can be a regenerative tool that reminds us of our human capacity for resilience in the face of all manner of disasters.

A version of this post was originally published in The Huffington Post, May 6, 2015

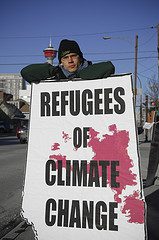

Photo credit: Flickr user Tavis Ford, CC BY 2.0)

Comments