As November creeps up on us, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton are accusing each other of stirring up racial divisions. From the start of his campaign, Donald Trump has stoked the fear of Hispanic immigration among the white working class, hoping to divide them from people of color.

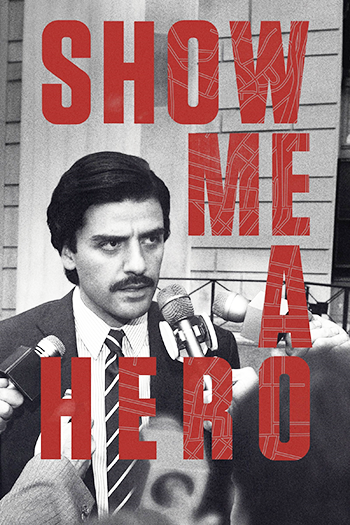

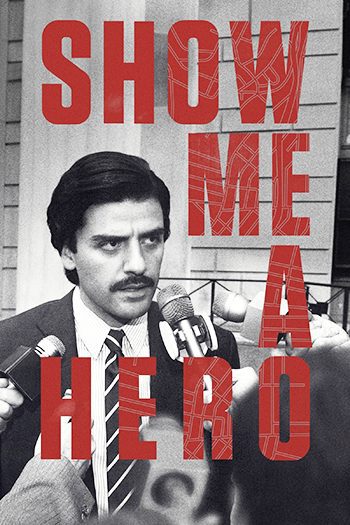

So it’s a tragedy that David Simon’s Show Me a Hero, one of the best limited-series TV shows of recent years, failed to get even a nomination for an Emmy Award earlier this month. The show has important lessons for what can be done when public officials try to divide their communities based on race. A character-driven docudrama, Show Me a Hero goes deep into the heart of a U.S. city in the middle of racial strife to portray how black and white citizens succeeded in reducing the consequences of years-long racial discrimination. The show is based on a true story that most viewers have never heard of, but need to know about.

Simon understands race and cities. His previous work, The Wire, an HBO series about criminal life in Baltimore at the beginning of the millennium, has influenced America’s perception of inner-city life. His HBO series Treme looked at post-Katrina New Orleans, dramatizing the devastation and tragedy that took place in one low-income area.

Hero goes back further to 1985, to yet another turbulent American city. In the first episode, we see developers and planners boarding a helicopter that is flying over Yonkers, New York, conversing about where to place low-income housing. As the camera sweeps high over the city, we take in the mansions and large open spaces in east Yonkers. And as they fly west we observe apartment buildings and row homes crowded together. Suddenly, we are at ground level meeting Carmen Febles, a Dominican immigrant and single mother getting out of a cab with her three children. On the way to their public housing apartment they are forced to trudge up several flights of stairs to avoid the intimidating drug dealer doing business in the elevator. It’s clearly the kind of building where parents worry that their children might be bitten by a rat or hit by a stray bullet.

The stage is set for a tale of lower-income black and brown families trying to break out of the slums—and the developers and white working-class residents who oppose them.

We quickly learn that as a result of a lawsuit brought by the NAACP, a federal district court judge, Leonard Sand, has ruled that Yonkers intentionally perpetuated segregation by concentrating almost all public housing in the city's overcrowded southwest, where most blacks and Hispanics lived. Sand has ordered the city to build 200 units of low-income housing in all-white neighborhoods to remedy past housing discrimination. The middle-class white residents, outraged at the outsiders bent on imposing their will on the community and fearful of living next to poor black neighbors, immediately begin organizing protests.

At a stormy city council session called by Mayor Angelo Martinelli in response to the court’s order, he urges the council not to appeal the ruling, arguing that the judge could impose fines that would bankrupt the city. But this just inflames the meeting’s protesters further, and they repeat their demands. “We’re not prejudiced, we just object!” yells one protester. Nick Wasicsko, a young, personable, ambitious but naive politician superbly played by Oscar Isaac, challenges the incumbent mayor in the next election. His vote to appeal the decision puts him on the side of the irate white residents, and he wins an upset victory.

The ensuing battle plays out largely among four white men—a smart idealistic NAACP lawyer, a tenacious judge, an architectural consultant, and the 28-year-old Mayor Wasicsko, who is the hero referred to in the title. (The show follows his conversion from supporter of the white residents to champion of the public housing families.) But as the drama picks up the pace in the final two episodes, the lens turns toward the families of color, the victims of discrimination, and it is here that the show becomes uniquely revealing.

Simon focuses especially on four women who maintain control of their lives (belying the stereotypes of the racists they confront). Carmen Febles never gives up her efforts for a better life for her children, even after her family is not chosen in the lottery for the new townhomes. Norma O’Neal is a 47-year-old black home-health aide living in the projects who demands to remain independent even while she is going blind from diabetes. Billie Rowan is a young woman who shows resilience as she struggles to raise two children without the support of their father, a local petty criminal.

These hard-working, protective parents are determined to lift themselves and their families out of poverty. Their public housing projects, neglected by management, are run-down, but their own apartments are nicely if modestly decorated. They are not simply victims nor are they saints. Though not always bound by their circumstances, they also don’t inevitably escape to “happily ever after.”

Perhaps the most sympathetic character is Doreen Henderson, a young black woman born in public housing but raised by her parents in a suburban home. Drawn back to the projects by her sister, she gets involved with a drug dealer, an under-treated asthmatic who can’t afford proper healthcare and ends up selling drugs to make money. Henderson evolves into a public-housing organizer who mobilizes other residents and builds relationships with sympathetic white neighbors, while at the same time fearlessly confronting the racists who oppose the building of public housing in white neighborhoods.

Though the racism of white residents is often on display, Simon does not make the opponents of the public-housing plan one-dimensional villains, either. Mary Dorman, wonderfully played by Catherine Keener, is a working-class woman reluctantly drawn to the opposition, who thinks the people of color who live in public housing will destroy her neighborhood. She eventually rises above her fear and reawakens her kinder nature after volunteering for a training program to help black families transition from public housing to their new townhouses. She meets Doreen and discovers a person not that different from her white neighbors.

Hero transcends the stereotypes of inner-city residents portrayed in many television dramas and books by depicting them struggling for change—and even changing a few minds. Even The Wire, Simon’s justly celebrated earlier show, didn’t do that.

While many viewers thought that The Wire presented an honest look at the realities of class, race, and urban life in the United States, the show actually distorted the picture in one significant way. Nearly all the black characters are from broken families, or are dangerous criminals or drug addicts, or depend on government aid—a group of people whose behavior and values separate them from the hard-working and mainly white middle-class characters on the show. Moreover, they are portrayed as having no capacity to mobilize and organize on their own behalf. The Wire’s unrelentingly bleak portrayal missed the solvable problems and the real causes for hope in Baltimore, and indeed in other major U.S. cities.

The Wire offers viewers little reason to believe that the lives of the people depicted in it could be improved either by individual initiative nor by collective action and changes in public policy. It offered viewers no hint that Baltimore has a growing movement to mobilize urban residents and their allies to address these problems. Similar movements exist in every major city in the country and have borne fruit in many ways. In my book about ACORN, Seeds of Change, I document how one group with chapters in cities across the country has improved neighborhood by successfully pressuring banks to provide homeownership opportunities for working people, getting local officials to put up traffic lights at dangerous intersections, and helping families avoid foreclosures.

Though not a path-breaking literary drama or sociological treasure chest like The Wire, Hero helps undermine two myths that the latter reinforced. One is that change in urban cities is impossible. The second is that the poor, especially the black poor and working class, are merely helpless victims with no recourse to collective action. Furthermore, the later show attests to the historical reality that social movements are necessary to address the problems in low-income neighborhoods.

The show has its weaknesses. The reasons given for the deterioration of public housing and the solutions provided are simplistic and inaccurate. For example, Yonkers officials agree with Oscar Newman, the white architectural consultant, who argues that the only solution for new public housing is townhouses, not high rise towers, because “nebulous” public spaces like stairwells and lobbies encourage crime and discourage residents from taking better care of their homes. So viewers don’t learn the best-kept secret about large, high-rise public housing projects: They actually provide excellent, affordable living places when well managed. They were allowed to deteriorate because of government practices and policies pushed by liberals, conservatives, and outside interests like the private-housing industry and anti-poverty groups. Originally designed for the working poor and young families starting out, public housing would instead become permanent housing for the very poor, so the private industry could cater to higher income working families.

Public housing became more unpopular politically, leading to a cycle of government cut backs, neglect, and underfunding, which, in turn, led to bad construction design, inadequate maintenance, racial segregation, and stigmatization. It also meant a further concentration of very poor black families living in neighborhoods lacking police protection, access to jobs, and bad schools.

What happened is a long and complicated story, but Hero’s creators certainly could have been more accurate in their brief sketch of it.

Hero also fails to fully depict the struggles waged by civil rights and fair housing advocates more than 20 years before its story begins, efforts that led to Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, which provided the basis for the lawsuit in the story. Of course that might be asking too much of one drama. The first episode does at least tie the civil rights movement to the court decision to end discrimination in Yonkers, noting that the suit was filed on behalf of the NAACP. In addition, an early scene has a young, white NAACP lawyer challenging a black NAACP leader for suggesting that fighting white resistance to integration may not be worth it. “Is the NAACP arguing against integration?” he asks incredulously. The NAACP leader responds by saying he’s not against it, but that he’s “just tired.”

Hero goes a step beyond the familiar tropes of low-income people of color suffering in inner-city residences—with little to no hope of escape. It offers a glimpse of post-civil rights history and pre-Black Lives Matters history, where the victims of discrimination and racism strategize to fight together for their own liberation. This great but underappreciated drama can give American viewers hope that different groups of people can work together to solve past injustices, a message that is sorely needed during this divisive presidential season.

Image courtesy of HBO.

The lawsuit that led to the court orders requiring both school and housing desegregation was initiated by the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice in 1980. Attorneys for the Division led the prosecution of the case which resulted in the historic 1985 decision of Judge Sand finding that the City had violated several civil rights laws. Thereafter, the Department, as plaintiff in the case, played a major role in developing the court ordered remedies, in addressing the City’s contemptuous resistance to the orders portrayed in the show, and tenaciously pursuing full relief into the 21st century. The NAACP intervened in the case and was an equally important participant, but the show and this article completely overlook the major role that the Civil Rights Division played in the case.

I agree. It’s important to remember the federal government can play an important supportive role in the fight for social justice.